(Reprinted from HKCER Letters, Vol.56, May-July 1999)

Hong Kong Healthcare and Finance Reform

Y.C. Richard Wong1

1. Introduction

The study Improving Hong Kong's Health Care System: Why and For Whom? (the "Harvard Report") published earlier this year makes it clear that the Hong Kong health system and its financing require reform. The Report also identifies many of the reasons - which in my view deserve to be taken seriously - why this is necessary and should not be delayed. The Harvard Report proposes a new approach to financing health care that would entail a total reform of the system of health care provision. Its core proposal centres on creating a universal mandatory social insurance system that would allow patients to choose doctors, clinics and hospitals. As a consequence, dollars would follow patients instead of being given directly to health care providers, as is the case at present. The current distinction and separation between public and private care will also basically cease to exist. The social insurance premium would be financed jointly by the patient and the public purse, and the new programme would include built-in income redistribution features to achieve equity objectives. While the Harvard proposal has obvious strengths and addresses some of the shortcomings of the present system, the report's proposal has serious theoretical and practical difficulties. In this article we discuss why the Harvard Report is correct about the necessity for change, but we also explain why the core recommendation of the Harvard Report is not a good solution for the problems of Hong Kong's health care system and go on to propose an alternative scheme.

2. Why is reform necessary?The Hong Kong health care system requires reform for a number of reasons. From a government-policy perspective, the main concern is the system's long-term financial viability. From a user's perspective, the greatest problem is quality of service. There are probably few consumers of either public or private health services in Hong Kong who, if asked, would say that they are truly satisfied with the services they have received. Users of public services complain of long waiting times, an indifferent service attitude and lack of choice, while those who go to the private sector face high costs and variable service quality.

Restrictions and barriers in the medical and health care professions seem to limit effective competition among private providers of health care. News reports of the barriers to entry of private clinics in public housing estates appear to be a case in point. While one should recognise the very visible improvements that have been made in the past few years in the public-hospital care sector, it is also important to note that the success has been achieved by means that are likely to be unsustainable. Many of the improvements have been facilitated by a generous provision of public funding that cannot be continued into the future. In a sense, the Hospital Authority (HA) has sown the seeds for its own future fall. Far-reaching health care financing reforms have to be introduced, and it is inconceivable that this can be achieved without reorganising the structure of health care provision in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong's spending on health care has risen substantially in recent years. Public health spending rose from 1.7% of GDP in 1989 to 2.5% in 1996. This growth is projected to continue into the future. The Harvard Report projects that public health spending will rise to between 3.4% and 4.0% of GDP by 2016, assuming that real GDP grows at the rate of 5% a year. This implies that, assuming that the Basic Law provision requiring that the increase in government spending be in proportion to growth in GDP is adhered to, government health spending will absorb 20-23% of the total budget in 2016, compared to the current figure of 14%. According to this scenario, the government will have to reduce spending on other areas in order to maintain health care services at their present level.

One may argue with the Harvard projections, but this is unlikely to be a useful exercise given the paucity of detailed statistics available at present. For this reason, the Harvard Report's recommendation that an Institute for Health Policy and Economics be established has great merit, because such an institute could provide policy makers with the necessary empirical analysis they need to make prudent reform decisions and to implement reforms successfully. One should also note that the paucity of data available today should not serve as an excuse for not reforming the system, since delaying reform could also have costly consequences for society. The present lack of detailed quantitative data therefore mandates an evolutionary reform strategy designed with built-in feedback systems so that the initial effects and results of reform can be used to modify policy over time.

One of the main factors behind the need for changes in the financing of health care in Hong Kong is the changing nature of Hong Kong society and the type of health problems that it will have to deal with. As Hong Kong becomes more affluent, the diseases affecting its citizens are changing. While in the past, the most pressing health problems were infectious diseases, in the future the prevalent problems will increasingly be chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, stroke and cancer and the care of the old. As Hong Kong's population ages as a result of lower birthrates and increased life expectancy, the proportion of medical services that the aged consume will rise significantly. The shift in demographics also means that greater emphasis should be given to prevention rather than to cure. Such an emphasis must be effected through patient-education, health-promotion, and disease-detection programmes. Early action to prepare for this trend is necessary.

While this may be the core long-term financial reason why reform is necessary, there are other pressing reasons for change. These mainly concern the quality of health care available in Hong Kong. In some respects Hong Kong can point to the high standard of health services provided to its citizens, but there are still many areas where the quality of service is variable and poor. To some extent this is the result of an inappropriate allocation of resources. Hong Kong has parallel public and private health systems that operate entirely separately and independently of each other. As a result, the overall delivery of health and medical services to patients is compromised. To a considerable extent, such compartment-alisation extends itself into the division between primary, secondary, and tertiary care. The fragmentation of service is highly inefficient and results in an overall deterioration of health care service quality.

In the public system, resources are primarily allocated by administrative means within the HA, with little guarantee that they will be provided where patients want them and where they are genuinely needed. The HA has improved its management of hospitals and provision of services in recent years. In some respects this has perhaps tended only to reinforce its own difficulties, since there is evidence to suggest that improvement in the services provided by public hospitals has attracted patients away from the private sector. The share of bed days occupied in the public hospital sector has risen from 90% to 92% since 1991.

Access to government health services is in practice free at the point of delivery. This is not to say, however, that users face no costs. In fact, the main direct cost to users is the queuing time involved in the use of public facilities. Consultation with a doctor frequently requires hours of queuing, in effect allowing access to government facilities to those who have time on their hands, while those who do not are forced to go to the private sector until they can no longer afford it.

The frequently poor standards of medical practice in Hong Kong can often be traced to the limited choices available to users. Within the government hospital system, patients are required to more or less accept what is given to them. Their only other option is to go to the private sector. Figures indicate that despite the "free" government outpatient services, the majority of consultations are with private doctors.

There is strong evidence that resources are poorly allocated even within the private sector. Private hospitals operate at well under capacity as a result of competition from a low-cost substitute available in the public sector. Since there is no meeting point between the public and private systems, there is often unnecessary duplication of effort. The private system also suffers from high costs, wide variation in the quality of treatment and inadequate competition caused by barriers to entry. The medical profession is highly protective of its interests everywhere in the world, and Hong Kong is no exception. Nevertheless, the possibility exists of reducing some of the barriers in order to redress the imbalance of market power in the private sector. For example, relaxing the restrictions on advertising of physician's service would enhance patients' ability to exercise their choice in a more informed manner. Allowing physicians free entry to practice in public housing estates would be in the interest of patients. Greater separation of patient consultations and the filling of drug prescriptions would benefit patients.

3. Financing possibilitiesIn practice there are only three basic approaches to funding health expenditure. Each approach entails a rather different way of organising health care services, and has different consequences for equity and efficiency. They are:

1. Direct public funding combined with public provision

Health care is provided directly by government out of tax revenue. Although the system may incorporate user charges, the bulk of the costs are borne out of taxation. If the tax system is truly progressive, as is the case in Hong Kong, then it will meet equity objectives. However, Hong Kong's narrow tax base and low tax rates make it difficult for the government to expand health spending without compromising the fiscal system. Moreover, the direct provision of health care by government is usually inefficient and unresponsive to patient needs. In Hong Kong direct government funding provides most of the finance for the hospital system, although elements of the other systems also coexist side by side with this system. Outpatient treatment is mainly carried out in the private sector.

The most significant point in favour of the existing system in Hong Kong is that it has a high degree of equity - no one is excluded from health care because of cost. The disadvantages of the government-funding approach are widely recognised. Hong Kong's government-run health care system is plagued by most of them and they are noted in the Harvard Report. Under this system, allocation of funds by administrative fiat leads to misdirection of resources, while access to the system at no financial cost at the point of use tends to create excessive demand for services. Without a proper monitoring mechanism it is difficult to control costs in such systems, and without financial incentives for staff service may be poor.

2. Fee for doctor with selective private insurance

Under this system, fees are paid to providers, either directly by users for services provided, or indirectly through private insurers out of premiums. Private insurance is unlikely to provide full coverage to all patient groups because of the problem of adverse selection, which makes private insurance financially not viable. A purely private fee-based system also faces problems; not least of which is restricted access to those without means. Demand is limited to those who can afford the fees charged. Resources are directed to those who can pay for the services, but at the cost of considerable inequity, since those without the means to pay are excluded from the system.

3. Insurance schemes funded fully or partly by public money

With funding under an insurance scheme, the cost of health care is covered by insurance premiums paid by users, perhaps supported partly or fully by government funds. Payments are made to health care providers by insurers to cover the cost of care provided. Under this system, which for the most part characterises the United States health care system, users pay for medical costs indirectly through their insurance premiums. An insurance-based scheme can be designed in principle to meet both equity and efficiency objectives and is therefore popular with most economists.

Insurance-based funding has its own drawbacks, however. One of the greatest difficulties associated with insurance systems is that they tend to increase costs as a result of the moral hazard problem. The use of deductibles and co-payments can mitigate some of the problems of overuse. In practice, though, it is unlikely that the problem of moral hazard can be entirely mitigated, because these systems do not operate in a vacuum and cannot be made immune from the reality of political tampering from powerful interest groups and misguided politicians. As a consequence, controlling cost can be a big problem. The examples of the United States and Taiwan are cases in point.

Moral hazard One of the most difficult problems that the provision of health care financed by insurance must face is that the insured may change his or her behaviour as a result of being insured. Moral hazard refers to the reduction in the incentive to take precautions as a result of having insurance. Insurance is intended to protect against the consequences of a possible undesirable outcome, such as illness. However, if an individual is protected against the outcome of an event, he has less incentive to take precautions to prevent the outcome occurring.

For example, let us suppose that a person develops a slight cough. This person knows that he is susceptible to bronchitis, and that the treatment for bronchitis is somewhat costly. If this person does not have insurance, he is likely to take precautions against aggravation of his illness in the hope that he will not have to pay for the expensive drugs that will be required should his cough develop into bronchitis. On the other hand, if the same individual, in the same situation, has insurance he is more likely to continue his normal behaviour, knowing that, should his cough develop into something worse, his doctor's visit and any necessary medication will be paid for by insurance.

The consequence of this type of behaviour for the insurer is that it raises the cost of providing insurance. If the premium is calculated on the basis of estimates of the probability of the undesirable outcome occurring prior to provision of the insurance, the actual probability will be higher, with the result that the insurer will lose money. The results of moral hazard can be reduced by various mechanisms, for example, by requiring the insured to pay the first part of any claim up to a specified amount, or by offering no-claims bonuses, which create an incentive for insureds to protect themselves from illness.

Adverse selection is another potential problem with voluntary schemes. A compulsory system can reduce the problems of adverse selection by spreading risk over the whole population. But one should note that the public health system is also prone to overuse by virtue of being a free service. Cost control is maintained through an inefficient rationing mechanism that eliminates patient choice.Insurers, since they operate primarily for profit, have strong incentives to control quality and cost of services and to prevent overcharging for and overuse of services. A body of private insurers will also form an informed counterbalance to the dominance of doctors. In fact, when the insurance system was first introduced in the United States, cost control and preventing overuse was not a problem, because the insurers provided an effective check against the perverse incentive of doctors to abuse usage and overcharge patients. However, in a landmark United States court case, the power of insurers to challenge the judgments of doctors in treating patients was severely curtailed. Since then it has been almost impossible to control health care costs in the United States.

Adverse selection The provision of insurance is complicated by the problem of adverse selection. If a person is healthy and believes there is little likelihood that she will become ill, she has little incentive to buy insurance. If she believes that she is likely to become ill, she has more incentive to buy insurance. This is a problem for insurers because, despite their best efforts to find out as much as they can about insureds' health prospects, individuals tend to know more about their own health than an insurer possibly can. As a result, adverse selection will take place, so that those insured will be more likely to suffer illness than the general population. One way to solve this problem is for insurance to be compulsory, so that risk is spread over the whole population, good and bad risks together. In a voluntary system, the effects of adverse selection can be countered by varying premiums based on the level of risk. Thus, health insurance premiums are in most cases determined according to the insured's age.

The main concern with a compulsory government subsidised and managed insurance scheme is that it is not a genuine market system organised from the bottom up, but a contrived socialist market system organised from the top down and controlled from the centre by a board consisting of politicians, bureaucrats, professionals and experts. The welfare of the public is entirely dependent on the decisions of this board, and any error it makes will be propagated throughout the system. It is a universal compulsory scheme from which the patient has no escape. As previously mentioned, however, a scheme based entirely on a private insurance market, however, cannot work either, because of the problem of adverse selection and its limited ability to address equity concerns. Furthermore, private insurance is unlikely to provide comprehensive coverage for those with bad health risks.Theoretically, health care should be financed by an insurance scheme because the incidence of disease in the population is uncertain. Without insurance the burden of health care expenditure may fall on those who cannot afford it. An ideal insurance scheme should pool cross-sectional risks across the population and be able to move resources intertemporally over an individual's life cycle.

Overuse of services

Insurance-based health financing in countries such as the US has suffered from severe difficulties associated with overprovisioning of services. Since the provider is paid by the insurer according to the procedures provided, it has an incentive to carry out as many procedures as possible, even when these are unnecessary. The user, who sees no direct relationship between his premium and the services provided, is unlikely to object to unnecessary services, such as tests. In the US, government insurance-based provision of medical services through Medicare and Medicaid led to the ballooning of medical costs for just these reasons.

This tendency can be countered by insurers taking steps to ensure that costs are controlled. Since under our proposal most insurance would be offered on a private commercial basis, there would be a strong incentive to control costs. This could be achieved through mechanisms such as fee schedules that limit maximum charges, or by requiring a second opinion before certain procedures are carried out. Insurers could also provide lists of preferred providers, known as preferred-provider organisations, which abide by cost schedules set by insurers. Individuals using those providers would enjoy cheaper insurance policies. Costs will also be kept in line by competition between insurers. Those that provided excessive services will find their costs and consequently their premiums rising, making them less attractive than other insurance schemes.

In a sense, all the three systems described above can be considered as forms of insurance scheme insofar as they all pool risks within the population, although in different ways and to varying degrees. In reality, all three systems coexist to some extent in every modern society. In part this reflects the complexity and difficult of finding a single system to meet the sometimes conflicting objectives of equity and efficiency in providing health care to different groups of patient populations. In health care the problems arising from (1) information asymmetry, (2) the many well-organised and powerful interest groups, and (3) the often emotionally charged nature of the subject, create numerous political stress points that make it difficult for society to adopt a rationally designed system that meets the standards of professionalism and is politically and financially sustainable in the long run. Each of the three systems we have discussed has its comparative advantages and disadvantages when serving different population groups. The presence of mixed systems throughout the world reflects the enduring relevance of this important observation. For this reason, it is unwise to try to create a single universal health care system. Indeed, it may be sensible to consciously design an institutional arrangement that is mixed in nature, which would in effect allow patients to choose among alternatives, and which would let each system compete with the others.

4. The Harvard proposalGiven the difficulties with each of the three systems discussed above, and the problems of the present health care system in Hong Kong, what is the way forward? The preferred option offered in the Harvard Report is a compulsory jointly funded insurance scheme with an expanded role for patient choice and market forces. Both the government and the patient will contribute to the cost of the premium. The proportion of cost sharing will vary with the economic situation of the patient in question.

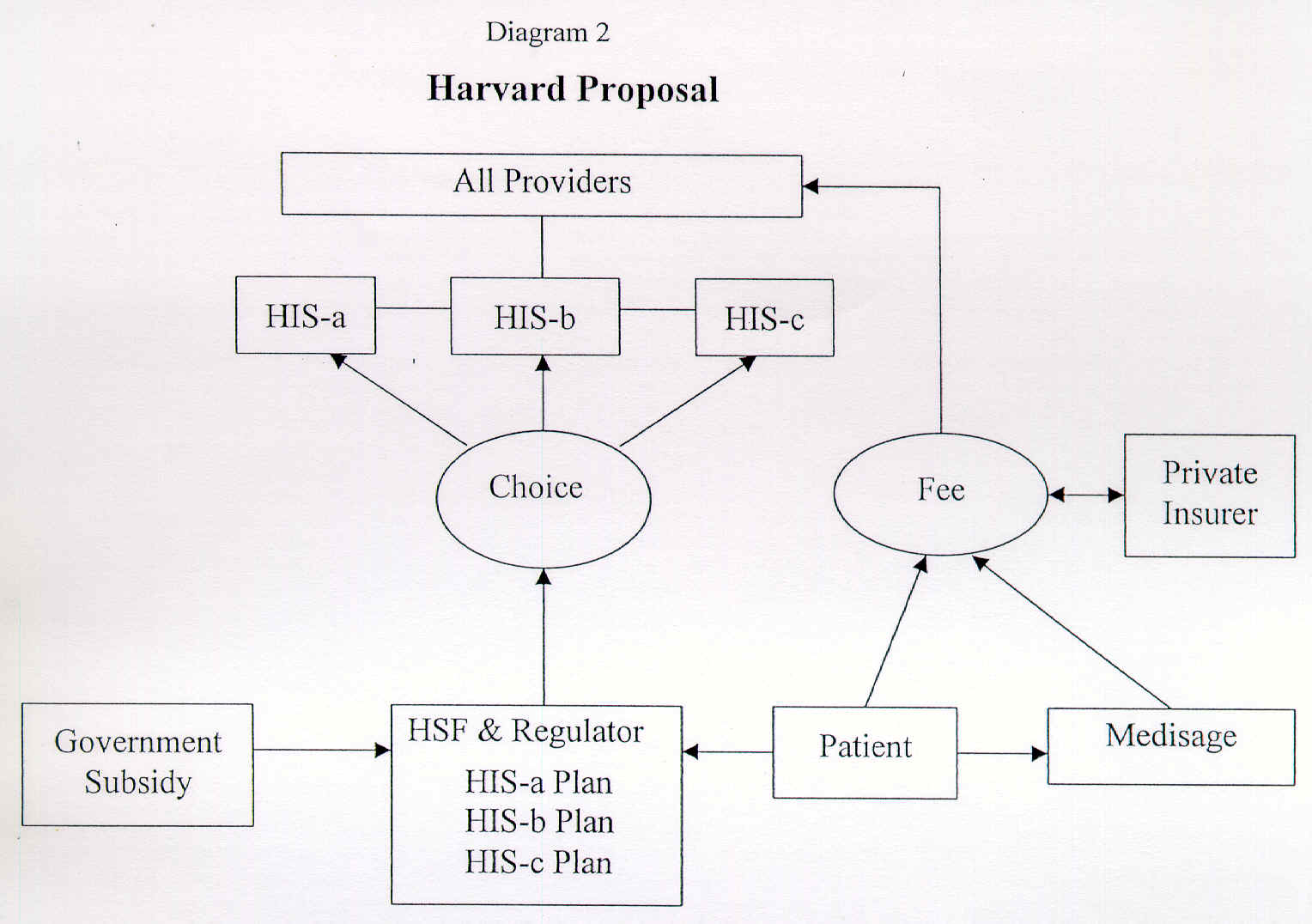

In essence, the Harvard Report proposes two insurance plans. The first is the Health Security Plan (HSPs), which covers major unexpected medical costs and pools risks within the population through a pay-as-you-go mechanism. The second is the Savings Accounts for Long Term Care (Medisage), which provides an individualised accumulative fund for purchasing long-term insurance coverage for old age or disability. A Health Security Fund (HSF) will be established to run the HSPs as a quasi-governmental body, and will be supervised and managed by a board with representatives of government, employers, employees and patients. This board will purchase health services from provider groups in both the public and private sectors.

Information asymmetry From the point of view of the user of medical services, one of the biggest problems with health care in general is obtaining information. The complexity of medicine and its technical nature tend to make it difficult for most patients to fully understand the treatment they are being offered. This, it is argued, prevents patients from making informed decisions, the basis of any workable market. Decisions are better left to those with the knowledge to make them, that is, doctors. The reverse side of this coin is that the monopoly of knowledge in the hands of doctors places them in a position to dominate the decisions-making process throughout the health system. In Hong Kong the lack of access to medical information is more acute than in many other parts of the world. It is frequently the case that doctors fail to explain treatments and medicines to their patients. User education is almost entirely lacking. And, of course, there is virtually no way that patients can access information on the quality of treatment offered by hospitals or doctors, except through word of mouth.

In order to create effective competition, more information will have to be made available to patients. It is often argued that one of the reasons doctors must dominate health care decision making is because the consumers of health care, unlike purchasers of other goods, are unable to fully understand the good they are receiving. Since the choice of medical care may be a life-and-death issue, it is vital that only the technically competent make decisions. Against this it can be argued that users do not need to fully understand medicine in order to make reasonably informed decisions. Consumers also make life-and-death decisions when, for instance, they purchase a car or buy a plane ticket. In both cases, consumers rarely fully understand the engineering of cars and aircraft. They are however, able to form a judgment of the reputation for safety of the make of car they purchase or the airline they fly with. In Hong Kong consumers could make much more informed medical decisions if the government were to collect and publish a far greater amount of information on the costs and outcomes of heath care providers than it currently does. Steps could also be taken to relax restrictions on advertising by the medical profession.

The Harvard Report offers a second stage of reform to be built on the basic reform of financing. Under this option, the HA will be reorganised into 12 to 18 regional Health Integrated Systems (HISs). The HISs would include regional public hospitals, which would be allowed to contract with private general practitioners and specialists to provide benefit packages covering preventive, primary, outpatient and hospital care. Private hospitals and physicians groups will also be allowed to participate in an HIS to provide benefit packages. The HISs are providers but they are not health maintenance organisations (HMOs) because the latter employ third-party managers to oversee and monitor providers' treatment decisions. The aim of forming these HISs is to overcome the existing compartmentalisation of health services by offering integrated services.It is argued that such a scheme will offer a number of advantages over the existing system. It is a simple scheme with a coherent concept that puts funds in the hands of the patient rather than the health care provider.

Maintaining and improving efficiency.

The Harvard scheme promotes risk pooling and provides equal insurance coverage to every resident, so that all are assured of health care. Subsidies are provided for those who cannot pay.Improving quality and efficiency.

The principle of "money following patients" creates equality for public and private-sector providers. Compartmentalisation of health services in the parallel public and private sectors would be removed. The HSF provides accountability to patients and the public, and a counterbalance to the dominance of doctors.Improving financial sustainability.

Built-in controls such as negotiated payment rates and demand-side cost sharing will help manage the government budget. Separation of purchasing and provision lays the foundation for competition between public and private providers and raises accountability and efficiency.Targeting subsidies.

Government resources can be targeted to areas where they are needed. Resources will be targeted through subsidies for premiums to benefit those who cannot afford health care, unlike the present system where the heavily subsidised public sector benefits rich and poor alike.Meeting the future needs of the population.

The MEDISAGE scheme provides for care of the elderly by funding the future costs of their care. These individualised accounts will be used to purchase insurance plans in old age, and if they are unspent will become a part of an individual's estate. In principle this is similar to Singapore's MEDISAVE account.Managing health expenditure inflation.

The Harvard scheme helps control inflation of health costs by separating purchasing and provision and by negotiating on payment rates. The "money follows patients" principle promotes efficiency through increasing competition, while deductibles and co-payments limit consumer demand.

5. The difficultiesA top-down market system.

Under the Harvard scheme, it is suggested that a central HSF be established to act as a purchaser for health services on behalf of the patient. The central role of the HA as both a buyer and provider of services would be changed to one where it is only a provider. It is not clear that this solution would necessarily result in any significant improvement in terms of competition among health service provider organisations, since the creation of a single central purchasing organ would in effect impose another administrative solution at the core of the new system. Rather than consumers, it would be this administrative body that decides what services should be covered by insurance, the rate of reimbursement and premium payments. In effect, the board would dominate the purchase of health services in Hong Kong, and would be able to impose its view of the health needs of Hong Kong's population on service providers. While patients might have a choice of doctors, they would not be able to choose an alternative system of health care providers; HISs would provide all health care services.Yugoslav labour cooperatives.

In the Harvard Report it is explicitly stated that the HISs are not HMOs because they do not employ third-party managers. One should note that the reason why United States HMOs employ third-party managers is that they are a business. Many HMOs are publicly listed companies. Third-party managers are employed to ensure that shareholder value is maximised and that the HMO is efficiently managed. If the 12 to18 HISs are really not HMOs, then what are they? The best way to characterise a quasi-governmental health service organisation is as a Yugoslav-style labour cooperative. Such organisations seek to maximise the wage bill per worker, rather than profits. They will not result in overall economic efficiency. Competition amony regional HISs, which, unlike corporations, do not seek to maximise profits, will not generate optimal savings for society. One should note that private hospitals in Hong Kong are not really business corporations either; rather they behave as labour cooperatives responsible to self-perpetuating management boards dominated by senior doctors and do not have shareholders to whom they are accountable.Under ideal conditions and if implemented as envisaged, the Harvard recommendations would create a Yugoslav-style socialist market system, the problems of which are well documented in the comparative economics literature. Such problems include inefficiency from a systemwide perspective, investment decisions being made to maximise per capita wages, labour mobility being minimised to protect the interests of the existing workers, and lack of innovation because property rights over innovations are not well defined. It is therefore not surprising to find that medical doctors working in United States HMOs are highly critical of their own system. Indeed, they would prefer a Harvard-style HIS.

6. Political Economy of ReformFor the Harvard recommendations to be implemented as envisaged it would require a total reorganisation of the system of health care provision and the creation of a radically different set of institutions. The provision of health care anywhere in the world is the locus of powerful conflicts of interest where entrenched groups are strongly motivated to look after their own interests in the name of the public good. Doctors, administrators and politicians are all in a position to significantly influence the way in which health care is provided. Health care provision is also a highly emotional issue, touching as it does on the fundamental interests of every member of the community. The fear of even relatively minor illness and its financial costs - not to mention of life-threatening medical conditions - is almost universal.

Given these powerful interests and fears, it is highly unlikely that any major reform of health care financing such as that envisaged by the Harvard Report will be accepted by all parties involved without strong resistance from certain quarters. Whatever its merits, acceptance of the Harvard proposal will require that interest groups be mollified with concessions, which will weaken financial controls and expand budgets. Such concessions may have the effect of fatally weakening the reformed system and of defeating one of its main objectives - effective control of the health care budget. This will lead to a situation in which costs can potentially escalate rapidly under the reformed system, so that within a short time it will become insolvent. This in effect has been the experience in Taiwan, where health financing has undergone a wide-ranging reform similar to that suggested by the Harvard Report for Hong Kong and where costs have increased sharply in a few years' time. The same is likely to happen in Hong Kong, given the absence of good health care statistics, which will give free rein to "informed prejudice".

If this happens in Hong Kong, the system will have to be refinanced by increasing premium contributions that will become politically divisive. As a consequence, service quality will begin to deteriorate, and eventually it may not be possible to allow for unrestricted patient choice. If this unfortunate outcome occurs, the entire reform effort would have been defeated, and the system of social insurance would have degenerated into nothing more than a scheme of earmarked taxes. In essence, the old system will be revived, and some of the key objectives of the reform - increasing user choice and controlling costs - will be lost. The public, however, will have been lured into paying more for its health care, although the system - and, within it, the type and quality of care available to them - will remain fundamentally unchanged.

7. ChoiceCare: an alternative proposalWith these reservations in mind, a more gradualist, but nevertheless fundamental, approach may be more appropriate for Hong Kong. This approach will retain elements of the existing system, while attempting to create a greater balance between the various elements, so that no one sector dominates, as is the case at present. Creating a better balance between the private and public sector will enhance competition among health care providers, providing them with an incentive to continuously improve the quality of health care service. It will also achieve the goals sought by the Harvard proposal - sustainable financing, enhanced user choice, and improved quality of service - without the political costs and with less of a chance of reform failure.

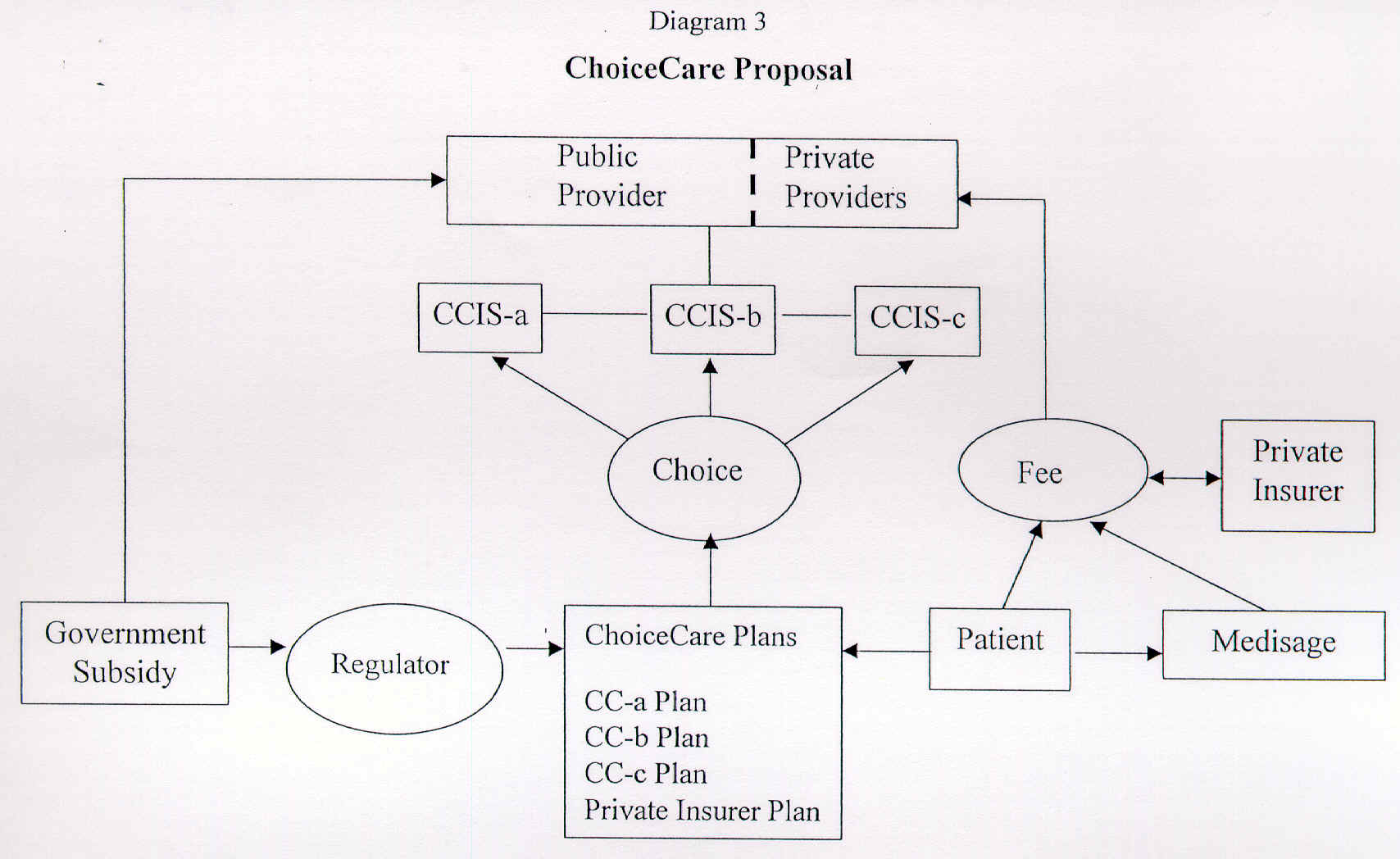

The key elements in our proposed reform would be (1) a system of voluntary subsidised insurance rather than a universal compulsory system and (2) a gradual integration of the public and private sectors. The voluntary subsidised insurance scheme will be called ChoiceCare.

Those who join the ChoiceCare scheme will receive a government subsidy on their basic-level premiums. The basic insurance plan will cover a fixed set of services that must be made available to all who wish to join. Should users require a greater range of services, they will be able to upgrade their coverage by making additional premium payments for additional services. Under this proposal, individuals will be permitted to purchase health insurance not from one central supplier as they would under the Harvard proposal, but from any number of possible suppliers. These could include not only hospitals and doctors' groups, but also insurance companies. The insureds will be permitted to choose their health care provider from among a number of options. These could include public hospitals, private hospitals, independent doctors or doctors' groups. Unlike the Harvard proposal, the creation of HMOs would not be precluded. Insurance companies that participate in the scheme could maintain a list of preferred doctors similar to preferred provider organisations (PPOs) in the United States. Since there is an element of government subsidy in this voluntary insurance scheme, health care providers and insurers will not be able to refuse to cover patients on a selective basis. Those individuals who do not join the government-subsidised scheme will have two choices - to use either the public or private systems.

Under this proposal, the public health system will continue to exist, but it will be open to a number of new competitive forces. Its budget will be reduced in proportion to the number of people who join the voluntary subsidised insurance scheme. But hospitals belonging to the HA will be able to recapture this lost financing by competing to provide services to those who have joined the voluntary insurance scheme, by, for instance, offering their own health care services and insurance plans. To create a level playing field the public hospitals will also be permitted and required to give access to private doctors to provide services to patients on a fee-charging basis. This will effectively transform HA hospitals into a system that provides two types of service. The first service type is a publicly funded free service similar to the service offered under the present system. It will be provided to those patients who did not join the voluntary insurance scheme. The second service is provided on a competitive basis, with providers charging market fees to fee-paying and ChoiceCare covered patients.

By forcing HA hospitals to compete with the private sector directly for patients the system will put in place a real and effective mechanism that will improve efficiency in what is otherwise a bureaucratically managed system. Most importantly, the HA will be changed from being a bureaucratic purchaser and provider of services to being the administrator of a system in which user demand will play a much greater role in financing. The HA would be subject to competition from other providers within a framework in which users will be able to choose their providers. Different forms of organising health care provision, such as doctors panels, PPOs, and HMOs, which are currently nonexistent or very limited in Hong Kong, could become available and will be able to compete in the market for clients.

The fundamental attraction of the ChoiceCare scheme is twofold. First, the scheme allows for more efficient allocation of resources among providers. As users will be able to choose both their providers and how to finance their health care, finance will follow the patients rather than being allocated on purely bureaucratic principles. Such a system imposes discipline on HA hospitals and also on the private sector because it too will be competing against a liberated HA sector. Second, the traditional role of the HA as provider of last resort for those without means will continue without fear of service disruption. These changes will not only provide an improved quality of service, but will translate into overall efficiency gains for the health care system and will result in net savings for society.

Since the subsidised insurance scheme is purely voluntary, there will be no coercive pressure to join, making it politically more feasible. Under this proposal insurers will be required to insure all those wishing to join, but insurers will be permitted to vary the premium depending on risk. Some people outside the scheme will find joining the ChoiceCare scheme very attractive. Those who rely on the existing public health system will be attracted to the higher-quality service and the possibility of choosing providers, such as hospitals and doctors. For those using the current private system, there will be the attraction of subsidised insurance. This will permit the user to choose not only his health care provider, but also his health care system. The option of moving from one system to another will help create a better greater balance between the different sectors.

The level of financing withdrawn from the public health system and the amount of subsidy provided to ChoiceCare participants will have to be estimated carefully so that the overall financial commitments of the public purse is known and controlled. In particular, the transfer of public funds from the public health system to ChoiceCare patients has to take into account the characteristics of the patients that join the ChoiceCare scheme. Caution may be necessary initially in determining the proper level at which to subsidise the ChoiceCare scheme, given that detailed medical and health cost figures are not available at present. Over time it will be possible to revise the commitment as experience is gained. It was pointed out at the very outset of this paper that the paucity of available detailed statistics mandates an evolutionary reform strategy. A strategy designed with built-in feedback systems so that the initial effects and results of reform can be used to modify policy parameters over time will be most effective in light of the small amount of data currently available.

A major attraction of such a reform strategy is that the relative desirableness of the ChoiceCare scheme versus the public health system can be controlled by the government through the relative generosity with which each sector is funded. The balance between the two systems can be maintained and changed over time through differential funding. Maintaining such a balance is desirable not only in terms of improving service quality, but also in terms of controlling the overall cost.

Patients who join the ChoiceCare scheme will not have the option of falling back on the public health sector. This is an important feature for controlling overall cost and avoiding the abuse of the public health system, which is probably pervasive at present. Currently, as a result of perverse incentives, many patients turn to the private sector for the treatment of major illnesses for as long as they can afford it, and when their money runs out they are shoved into the public sector. This is of course the extreme manifestation of the major weakness of the present health care system, under which over 80% of outpatient treatment is undertaken by the private sector, but over 90% of inpatient treatment takes place in the public sector.

Unlike the Harvard scheme, ChoiceCare would not require that insurance be offered by a central body. Rather, multiple providers will offer insurance policies. The precise terms and conditions of services provided will be determined by the market of patients, providers, and insurers, not by any central administrative body. There will be an element of government oversight of the insurance system to ensure order in the market and fairness to consumers. Insurance schemes will be regulated and monitored by the government to guarantee that they meet minimum standards of coverage, service, financing and reimbursements.

ChoiceCare

- voluntary subsidised insurance

- government subsidy of basic insurance premiums

- upgrading of insurance coverage possible at higher premiums

- many sellers of insurance permitted, including hospitals, doctors' groups and insurance companies

- patients have choice of providers, including public and private hospitals, doctors' groups or individual doctors

- public and private systems will coexist with ChoiceCare

- regulation of system by government to ensure high standards

- possibility to introduce medical savings for serious illness and old age

- flexibility allows for policy adjustment as system evolves

In the future, it may be necessary to introduce a system of pre-funding health care expenditure through the creation of individual savings accounts to meet the needs of long-term care for old age and disability, and to meet catastrophic needs. But pre-funding should only be introduced after the entire health care system has achieved a better balance between and greater integration of the public and private sectors. Such a development would be appropriate after the ChoiceCare scheme has become a significant factor in promoting the transformation of health care provision. At that point, the public will then be more readily convinced that pre-funding is not a pretext for raising taxes in the absence of any patient representation in determining the kind of care they demand.There is no single ready-made answer to any of society's health care problems. As Hong Kong changes and becomes more affluent, rather than becoming simpler, its health problems will become more complex and difficult to resolve. In this respect, a diversified system that offers a number of options is the best solution. Not only will Hong Kong need to provide hospital and outpatient services, it will also have to pay much greater attention to health education, prevention, and community medicine. This proposal will maintain equity while enhancing quality and efficiency by diversifying the health care system, and creating a situation in which the various elements in the system are more balanced. It would also pave the way for pre-funding health care expenditure so that Hong Kong at some point will not have to rely solely on a pay-as-you-go system for financing health care services. Above all, this option offers a gradualist programme of change that reduces the risk of failure as a result of initial miscalculation of costs and permits policy adjustments as the system evolves.

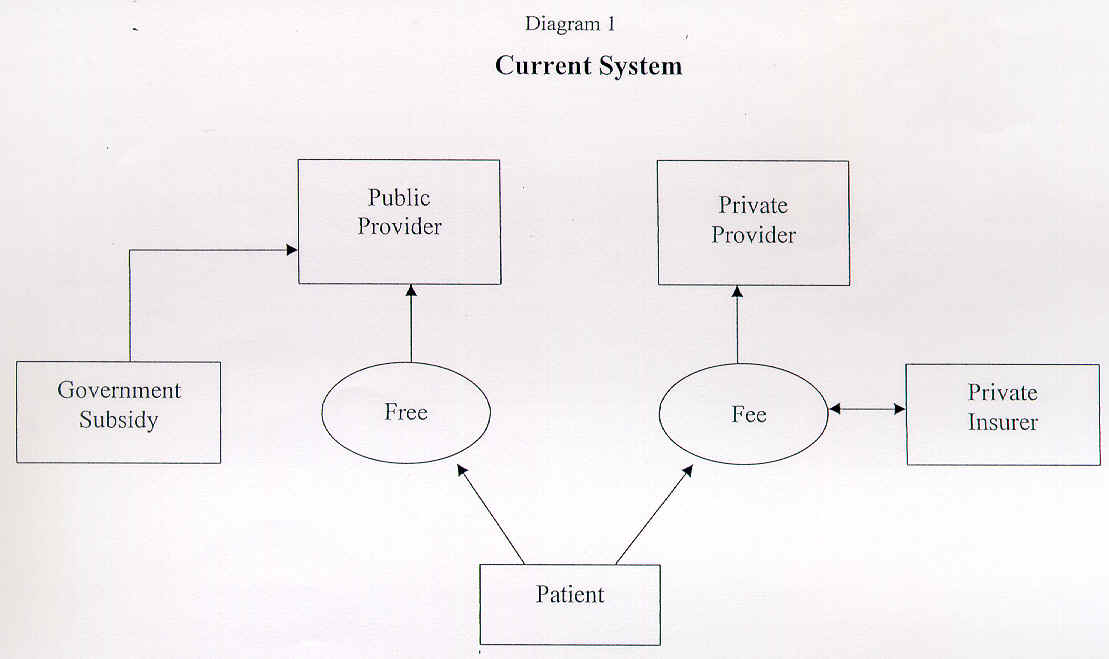

Diagram 1 shows the current situation with parallel public and private health care systems. The user has the choice of either the free public sector or the fee-paying private sector.

Diagram 2 shows the Harvard proposal. The patient will choose among various HIS plans, although all patients will be within the same compulsory system. Fees will follow the patient to whichever provider he chooses. All providers will operate under the same system, with the HSF as the single purchaser of services.

Diagram 3 shows the ChoiceCare Proposal. Patients will choose from a range of subsidised insurance schemes. These may be offered by both public and private providers as well as insurance companies. Public and private sector providers will be integrated, although not completely. Fees will follow the patient in the ChoiceCare system, who will also have the option of going to the traditional public or private sectors. ChoiceCare plans will be regulated by the government.