(Reprinted from HKCER Letters, Vol. 55, March-May 1999)

The Tyranny of Numbers

Wing Suen

Seldom has a single number swayed public opinion so swiftly. Following the release of an estimated figure of 1.68 million people in China eligible to settle in Hong Kong under the Basic Law, support for the Court of Final Appeal ruling on their right of abode collapsed almost overnight. The floodgate scenario was turned into an imminent possibility. The question was no longer whether the door should be closed, but how. The Chief Executive vowed to take decisive action, a promise kept through the decision to request an interpretation of the Basic Law by the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress.

It is hard to argue with numbers. If 1.68 million people were added to the Hong Kong population, it is a matter of simple arithmetic to project the extra demand for education, housing, medical care, welfare assistance, and, if you like, oxygen. A large number multiplied by any reasonable number is a large number, and it is a foregone conclusion: Hong Kong cannot cope.

Quantitative reasoning is an extremely useful input to policy making because it is systematic and replicable. One must bear in mind, however, that numbers are no more authoritative than the process generating them or the assumptions behind them. In a tyranny political authority cannot be questioned, but in Hong Kong we should not allow ourselves to be tyrannised by numbers when their authority is open to question.

Randomized ResponseThere are two situations in which a person should be skeptical of a statistic: when he does not know what is behind the number, and when he does. Many people do not understand how the government's estimate is arrived at because it relies on

a relatively unfamiliar procedure known as randomized response. Randomized response is a well-respected survey methodology used to elicit answers to potentially embarrassing questions. It is not some super-sophisticated method which is impossible to understand and which one has to accept on faith.

Suppose I walk into a lecture hall of 100 students and ask, "How many of you have ever visited pornographic web sites?" Chances are, very few students will volunteer to answer truthfully. Instead I could mix the sensitive question with an innocent question and say, "If you have visited a pornographic web site before or if you have an ID number that ends with an odd digit, please raise your hand." In this case, answering truthfully becomes less embarrassing because other people cannot tell whether the answer is a response to the sensitive question or to the innocent question. This survey method will not identify who have or have not visited pornographic web sites. Nevertheless, it is possible to deduce the total number of visitors. For example, suppose 80 students raise their hands. I reason that, on average, 50 out of the 100 students will have ID numbers that end with odd digits. Thus, out of the other 50 students, 30 students must have raised their hands because their answer is "yes" to the sensitive question. I conclude that 60% of the students have visited pornographic web sites.

Once the logic behind randomized response is understood, consider how this method is applied in the government's survey. The sensitive question is related to the number of children born outside marriage who are still living in mainland China. The innocent question is about the number of taxi trips taken in the past seven days. The interviewee is supposed to answer one of these two questions depending on the outcome of a randomization device, with a 60% chance that the sensitive question will be answered, and with a 40% chance that the innocent question will be answered. If we represent the average number of children born outside marriage per person by x, and the average number of taxi trips taken by y, then the average response to the randomized question will be

z = 0.6 x + 0.4 y

The value of z can be directly tabulated from the results of the survey. The value of y is estimated from a prior survey. Given these two values, the number of children born outside marriage (x) can be recovered from the equation above. There are standard formulas for calculating the sampling errors from a randomized response survey. Sampling errors are the errors that arise because only a fraction of the population (instead of the full population) have responded to the survey. The government has indicated that its estimates are subject to sampling errors of 5 to 10%. In a large scale social survey, however, sampling errors are typically much smaller than non-sampling errors. Non-sampling errors may arise, for example, if the survey targets respondents who are likely to have children still living in China.

Non-sampling errors may also arise when interviewees fail to understand or cooperate with the instructions. One important practical guide for minimizing this kind of non-sampling error in a randomized response survey is to select an innocent question such that the distribution of answers to this question are roughly similar to the distribution of answers to the sensitive question. In terms of our symbols, x should be approximately equal to y. Of course, we do not know what x is. But suppose we take the estimated figure of 520,000 children born out of wedlock at face value. Given that the size of the population aged over 16 is about 5.5 million, we expect that the value of x is no greater than 0.1. The average number of taxi trips taken can be estimated fairly easily from a published government report on taxi waiting time, which suggests that the value of y is about 0.52. In other words, y is an order of magnitude larger than x. This reflects one simple fact: riding a cab is a lot more common than having an illegitimate child.

To see why this flaw in survey design is important, suppose 10% of the interviewees always choose to answer the innocent question (regardless of the outcome of the randomization device) because they feel the sensitive question is an intrusion into their privacy. Of 100 interviewees, one should normally expect 60 to answer the question on illegitimate children, but 6 out of these 60 choose to avoid the sensitive question and answer the question on taxi cab rides instead. Since the answer to the taxi cab question is on average larger than the answer to the illegitimate children question, this will introduce an upward bias to the estimate of the number of children born outside marriage.

Table 1 shows the magnitude of the bias for various values of x. If 10% of the survey respondents fail to follow the interview protocol and always answer the taxi question, the upward bias in the estimate of the number of children born out of wedlock is much larger than 10%. For example, suppose the true number of these children is 275,000. Then the non-sampling bias can produce an estimated figure of 533,500---an error rate of 94%.

Table 1 Bias from the Avoidance of the Sensitive Question

Actual

Estimated

x

number

x

number

percent bias

0.01

55,000

0.061

335,000

510%

0.02

110,000

0.070

385,000

250%

0.03

165,000

0.079

434,500

163%

0.04

220,000

0.088

484,000

120%

0.05

275,000

0.097

533,500

94%

0.06

330,000

0.106

583,000

77%

0.07

385,000

0.115

632,500

64%

0.08

440,000

0.124

682,000

55%

0.09

495,000

0.133

731,500

48%

0.10

550,000

0.142

781,000

42%

Ten percent of the interviewees are assumed to always answer the innocent question.

The population base is assumed to be 5.5 million.

Internal and External ConsistencyIt is not possible to know how many interviewees actually avoided the sensitive question. Thus the precise magnitude of the non-sampling bias cannot be directly assessed. Nevertheless, Table 1 shows that this type of bias is potentially very serious. In such a situation, we must carefully check the data with other sources of information to make sure they are consistent with one another.

The government survey originally contained an internal consistency checking mechanism by dividing the sample into two groups. One group of interviewees were questioned by the randomized response method, while the other group were interviewed by direct questioning with strict protocols to guarantee anonymity. A number of researchers have compared these two approaches by validating the survey estimates with the true records, and they find that randomized response does not significantly outperform direct questioning in eliciting truthful answers from respondents. One would therefore expect the survey results from the direct questionnaire group to provide useful information for estimating the number of children still living in China. However, the government claims that survey results from this group is "unsatisfactory".Half of the data is therefore discarded after the fact! I will not assume the data were considered unsatisfactory merely because they produced an estimate which was too low for the government's liking, but one should nevertheless maintain some healthy skepticism when one does not know what is behind the data.

The government conducted two earlier surveys in 1991 and in 1996 on the number of children living in China with parents who are Hong Kong residents. Both surveys give an estimated figure of slightly over 300,000, which is substantially lower than the current estimate. In these two surveys, the definition of "children" is left unspecified. The interviewees might or might not have included children born outside marriage when responding to the survey questions. For people whose marriages were customary and were not properly registered (primarily the older generation), having children "outside marriage" is not really such an embarrassment. One would therefore expect that most children who fall into this category were already properly counted in the earlier surveys. The discrepancy between the earlier surveys and the current survey is unlikely to be explained by children born in unregistered marriages.

Can the discrepancy be accounted for by the children of Hong Kong men who keep "mistresses" in China? This is unlikely. China did not open its doors until 1978, and very few Hong Kong men visited China on a regular basis until the mid 1980s. Even if keeping a mistress and maintaining a second home in China is a common practice, the children in such homes should be less than 20 years old. However, the government has indicated that less than 30% of the children counted in its survey are aged below 20. The number of young children is simply not enough to account for the huge discrepancy between the 1996 figure of 321,000 and the 1999 figure of 692,000.

Finally, the estimated figure of 520,000 children born outside marriage and living in China simply does not pass the "smell test". This test says that if a number smells foul, then do not put your money in it. There are approximately 5.5 million people in Hong Kong aged over 16. Suppose among those who have illegitimate children living in China, each have on average two children. Then, according to the estimated total number of 520,000 children, of every 20 persons in Hong Kong---men, women, students, the elderly---one would have children living in China born outside marriage. I will not bet my money in such a statement.

Soviet JewsNot so long ago, when the Hong Kong government was lobbying Britain to grant its subjects the right of abode, everyone was familiar with the distinction between the right of abode and immigration: giving three million Hong Kong people the right of abode does not mean that these three million people would flood into Britain. This distinction is seldom mentioned today. Perhaps we are so proud of ourselves that we honestly believe anyone living in the mainland would want to settle in Hong Kong if given the chance.

Of all the individuals in China who have or will have the right of abode in Hong Kong, how many will want to come? One hundred percent is certainly a wrong answer, but is the truth closer to 70% or to 40%? No one can be sure. The migration of Soviet Jews, however, can shed considerable light on this question.

The Law of Return in Israel guarantees any person of Jewish origin the right to settle in the Jewish state. Before the collapse of the Soviet Union, this law was of little consequence for Soviet Jews because of emigration restrictions. Following the end of emigration control in the post-Soviet era, large numbers of Soviet Jews immigrated into Israel under the Law of Return. The situation is quite similar to the one raised by the Court of Final Appeal ruling in Hong Kong: a large pent-up demand for migration followed by a sudden change in immigration/emigration laws.

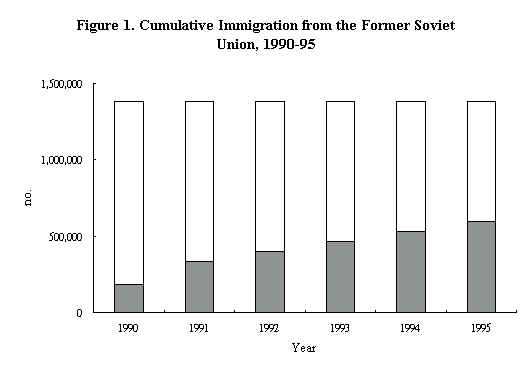

There were about 1.38 million Jews living in the Soviet Union in 1989. Figure 1 shows the cumulative total number of Soviet Jews who immigrated to Israel following the break-up of the Soviet Union. In the first year when emigration controls were lifted, 185,000 individuals, or 13% of those eligible to return, migrated to Israel. The total number of immigrants rose to 398,000 in 1992 and to 597,000 in 1995. In other words, in the six years after Soviet Jews gained the freedom to leave, about 43% of the total possible actually moved to Israel.

The difference in the level of economic development between Israel and the former Soviet Union is roughly the same as that between Hong Kong and mainland China. Thus the incentives for Soviet Jews to go to Israel should be as strong as the incentives for mainland Chinese to come to Hong Kong. According to this comparison, about 40 to 50% of the Chinese residents with the right of abode in Hong Kong under the Court of Final Appeal ruling would have actually come to settle in the next seven years. This estimate is far below the government's assumed figure of a 100% settlement rate within three years.

Several factors suggest that the settlement rate for the mainland Chinese would not be exactly the same as that for the Soviet Jews. First, the mainland Chinese with right of abode in Hong Kong typically would have had a parent living in the territory. This tends to raise their incentive to come, at least for those children born within marriage. On the other hand, these Chinese residents would not be able to bring their own spouse and children to Hong Kong (at least until they themselves have become Hong Kong permanent residents). Separation from the family tends to discourage migration. On balance, compared to the Soviet Jews, probably those younger mainlanders without their own families would have been more likely to come to settle, while the older mainlanders who have their own families would have been less likely to come.

Second, Soviet Jews tend to be more educated than native Israelis, while mainland Chinese with right of abode in Hong Kong are generally less educated than the local population. In Hong Kong, the wage structure is more dispersed than is the wage structure in mainland China. Thus the gain from migrating from China to Hong Kong is higher for a skilled labourer than for an unskilled labourer. If this is the case, a low-skilled worker in mainland China probably has less incentive to migrate to Hong Kong than a high skilled Soviet Jew has to migrate to Israel. Both factors then suggest that the fraction of eligible mainland Chinese who would have actually migrated to Hong Kong was unlikely to exceed 50%.

The 1.2 Billion FallacyBig numbers seem to cause big problems, and big problems seem to call for big solutions. The Hong Kong government steadfastly refused to consider the possibility of less drastic solutions to the immigration problem. At present, for example, Hong Kong cannot control its daily intake of 150 legal immigrants from China. If Hong Kong takes control, the quota can be used more efficiently to accommodate those people who have right of abode. It is distressing that the government dismissed such proposals on administrative grounds, when the solution proposed may seriously undermine human rights, the rule of law, and the principle of "Hong Kong people ruling Hong Kong." All the more distressing is that the decision was made without careful consideration of the validity of the data on which it was based or of alternative interpretations of its implications.

Some foreign investors have been lured into China by the huge size of its population. The logic seems simple enough: "Even if a tiny fraction of 1.2 billion people buy my products, I will be rich". Many investors have learned their lesson since: there is a lot more behind the awesome figure of 1.2 billion. Big numbers can be overwhelming. The government's estimate of 1.68 million people flooding into Hong Kong is indeed intimidating. But we should not be tyrannised by big numbers alone, especially when this number seems to hide more than it reveals. Big numbers don't necessarily lead to big solutions. The devil is in the details.