(Reprinted from HKCER Letters, Vol.34, September 1995)

Gas Regulation and Competition in Hong Kong

Pun-Lee Lam

In July 1995, the Consumer Council of Hong Kong published a report, called Assessing Competition in the Domestic Water Heating and Cooking Fuel Market. The report attacks the non-interventionist and safety policies of the government as having helped the towngas company, Hong Kong & China Gas (HKCG), to earn "excessive profits," to the detriment of its customers. The report proposes a restructuring of the market, with an aim to introducing competition into the market. This article assesses the source of market power of HKCG and points out some of the methodology pitfalls found in the report. Based on the experiences of gas industry restructuring in the United States and the United Kingdom, the author suggests ways to introducing competition into the fuel market in Hong Kong.

Regulation-Induced Market PowerTo support its argument for government control and in order to widen the market, the Consumer Council provides much evidence of HKCG's dominant position within the current market and the abuse of its market power. At the very beginning, the report argues that there is imperfect competition among different energy suppliers in the market due to safety, technical, and cultural factors.

A turning point in the history of Hong Kong's fuel market which was not mentioned in the report occurred in 1981. After the publication of the Report on the Safety and Legal Aspects of Both Town Gas and LPG Operations in Hong Kong (1981), the market concentration of the fuel market changed dramatically. Following the recommendations in this report (1981), the government introduced a piped gas policy to discourage the use of bottled gas in domestic dwellings. At the same time, it encouraged the upgrading of sub-standard gas water heaters. The Gas Safety (Gas Supply) Regulations prohibited the installation of any gas mains for the conveyance of LPG along or across a road. The transmission of LPG under public roadways was banned completely. Consequent to this prohibition, it was required that a special storage depot be built near to a housing estate to secure supply of LPG. These constraints imposed by the government in the 1980s raised HKCG's competitive power and directly led to the company's success. Since the publication of the Safety Report (1981), the business of HKCG expanded rapidly and its book rate of return increased from 10.1 percent in 1981 to 28.7 percent in 1992.

Despite the fact that HKCG has been earning attractive profits for years, the Hong Kong government refused to regulate the company, based on the belief that substitutes, such as electricity and bottled and piped LPG, are available for consumers to choose. It has been argued by the government that competition among these alternative fuel suppliers would lower the prices charged by HKCG down to their competitive levels.

From a historical point of view, the success of HKCG is, to a large extent also a result of innovative activity undertaken by the entrepreneurs of the company. The high rate of return enjoyed by the company is partly due to safety regulations and partly due to the reward, or risk premium to the company's innovative activity. In a market without entry restrictions, firms introducing unwanted products lose income and go out of business whilst those who can successfully introduce new products are rewarded by returns higher than the competitive level. If competition really exists in the fuel market, there is no reason for the government to eliminate a firm's income from innovative activity, while not compensating those firms who suffer losses from unsuccessful innovations. Such asymmetric treatment dampens the incentive to innovate.

From a different angle, however, if HKCG's success can be attributed to favorable policies (on safety) adopted by the government, and the right to build transmission networks under public roadways (i.e., pipeline right of way) without paying a commensurable price, then there may be a case for government intervention. Government intervention is needed to prevent the natural monopolist from using its market power over the network to exploit consumers. The benefits derived from the network should be extended to consumers and other fuel suppliers. In the United States, the origin of the regulatory contract between the regulator and a public utility was also based on this belief of protecting consumers from the abuse of monopoly power. When imposing regulation on the natural monopolist, however, the regulators are, under constitutional law not to confiscate private property. Regulated firms are entitled to earn a "fair" return on their prudent investment.

Some Methodology PitfallsWithout addressing the issue of whether the existing fuel market is monopolistic and inefficient, the author fully supports the notion of introducing competition into the fuel market in Hong Kong. The towngas company should also welcome the move if its high profits are due to its competitive advantage, rather than the abuse of its market power, as advocated by the Consumer Council. Unfortunately, the report published by the Consumer Council is flawed with problems of methodology.

(1) On relative price increases

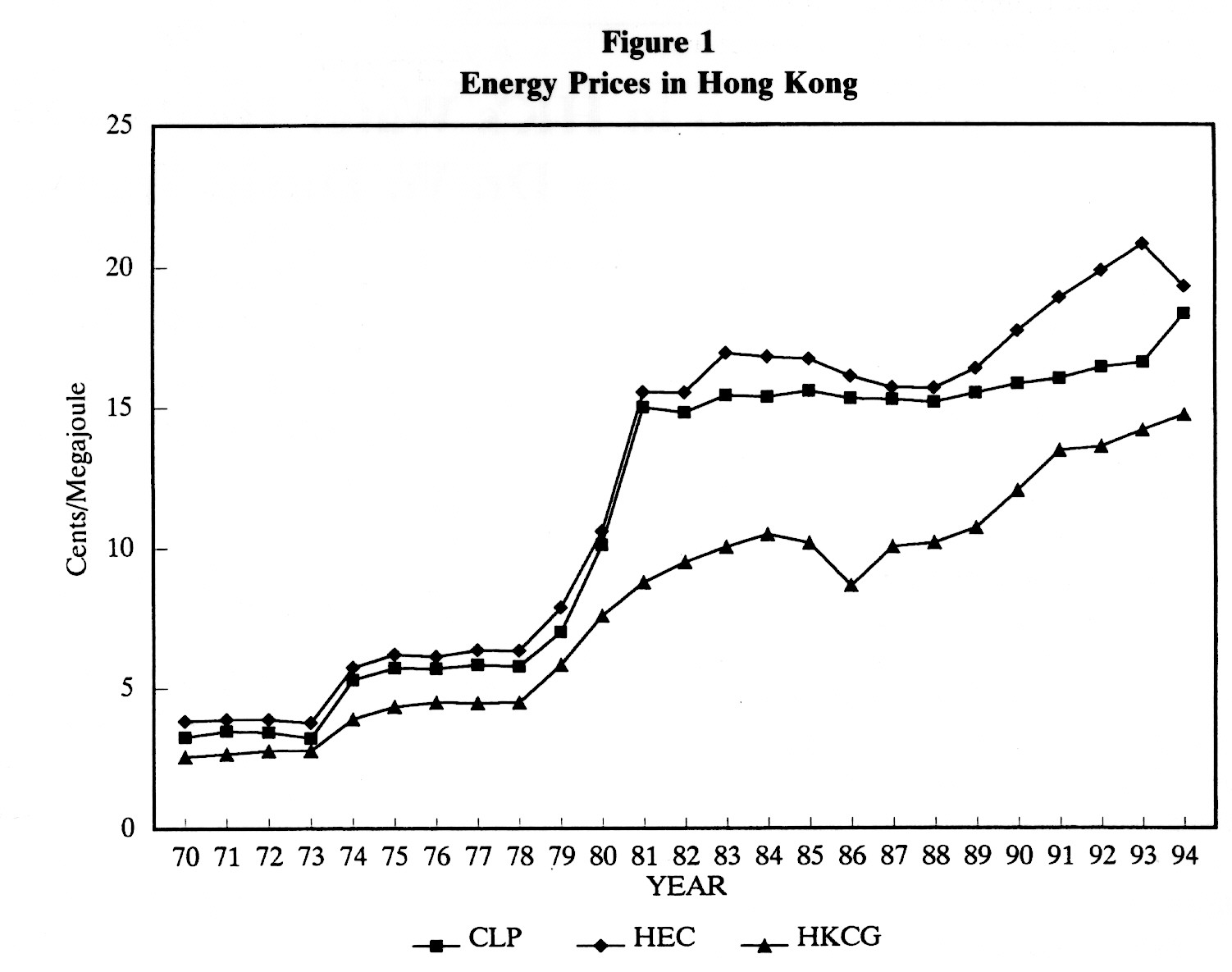

When comparing the relative performance of the three power utilities, the report only considers empirical data over the last ten years (1985-1994). Had a longer period been considered, the situation would change entirely. In the 1980s, the two electricity companies (CLP and HEC) engaged in a large-scale construction of coal-fired generators. Substantial capital expenditure was required to meet the construction costs. This, coupled with rapid oil price increases, caused the two companies to increase tariffs sharply in the late 1970s and early 1980s (see Figure 1). Since the report only considers the period from 1985 to 1994, after the commission of coal-fired generators, electricity prices charged by CLP and HEC only increased by 12.4 percent and 28.7 percent respectively. However, HKCG's price increases were not higher than those of CLP and HEC if we measure price increase over a longer period of time.

(2) On price elasticity of demand

To support the notion of limited substitutability among alternative fuels, the report has estimated the price elasticity of demand for towngas. To our amazement, the estimation of price elasticity is crude and quite wide of the mark. Estimation is simply based on annual data on inflation adjusted towngas price and quantity consumption per household. By comparing the annual percentage change in quantity with the corresponding percentage change in price, the report then concludes that "electricity and LPG are not close substitutes for Towngas with consumers having limited ability to switch in response to price changes" (p.61). Such crude measurement has also resulted in positive price elasticity of demand for some years.

In fact, changes in quantity consumption of towngas over time were not simply due to price changes. There are other important factors affecting demand for towngas. In addition, cross elasticity, rather than price elasticity, should be estimated to assess substitubility among different products. A basic approach to estimating elasticities is to formulate an econometric model which includes important factors affecting quantity consumption of towngas. With scanty information available, the author has tried to use a simple demand model to estimate elasticities of towngas, based on annual data (in real terms) from 1973 to 1994. The results shown in Table 1 suggest that demand for towngas is price inelastic but highly income elastic. Cross-elasticity between towngas and LPG is low. The negative sign of the variable CLPPRICE suggests that electricity and towngas are complements, rather than substitutes. This may be caused by the small sample size and possible multicollinearity problem. The dummy variable is positive and significant, which suggests the Safety Report (1981) has great impact on the consumption of towngas. Although our estimations are hampered by the limited information available, and the model proposed only includes factors on the demand side, the results still indicate that the rapid expansion of towngas consumption was mainly due to the improvement of living standards (INCOME) and government safety policy on fuel supply (DUMMY).

(3) On cost of equity capital

The capital asset pricing model (CAPM) is employed by the Consumer Council to estimate the cost of equity capital. The Report (1995) estimates the risk-free rate and market returns based on data from a brief period of three years (1992-1994). The period selected is too short for any proper estimation and is also inappropriate. During that period, share prices in Hong Kong fluctuated drastically. The choice of such an exceptional period to estimate risk-free rate and market returns would undoubtedly bias our results.

The author conducted a similar study on the costs of capital of the power utilities in Hong Kong, based on monthly data from 1977 to 1992. The results are shown in Table 2. The risk factor (beta value) and cost of equity capital (or required rate of return on equity capital) of HKCG is higher than CLP and HEC. This is not unexpected, as the returns of the two electric utilities are regulated by the Scheme of Control, and their development funds can stabilize the returns of the two companies. From our results, despite the control imposed on CLP and HEC, all three power utilities earned returns in excess of their equity costs for the period 1979 to 1992 (see Table 3). Therefore, government regulation may protect, rather than eliminate, the excessive returns earned by monopolists.

The report also compares the rate of return of power utilities in Hong Kong with those in other countries. Such comparison of nominal returns is inappropriate, as the market and political risks are different in different places. The risks associated with the market structure and the regulatory system are also different. Worse still, historically, the inflation rates in Hong Kong are much higher than in these other countries (Table 3); the use of nominal returns (instead of real returns) inevitably exaggerates the profitability of utilities in Hong Kong.

(4) On capital structure

The report compares the capital structure of HKCG with the other two regulated electric utilities. While CLP and HEC are highly leveraged, HKCG did not issue any debt until 1993. The report then concludes that pure equity financing by HKCG is conservative and an inefficient financing policy, as equity financing is typically more costly than debt financing. However, finance theory has shown that debt financing does not change a firm's overall cost of capital. Furthermore, the high debt-equity ratios of the two electric utilities in Hong Kong are induced by the regulatory system itself.

Under the existing Scheme of Control imposed on electric utilities, the permitted rates of return on equity and debt capital are different. At present, the permitted rate on assets financed by equity is 15 percent, while the permitted rate on assets financed by a development fund is the same as that for debt-financed capital -- both are fixed at 13.5 percent. As the maximum interest rate payable on long-term loans is 8 percent, while the interest rate charged on the development fund is fixed at 8 percent, both are lower than the permitted return of 13.5 percent; the government in effect subsidizes the two electric utilities through debt financing. The two companies can enjoy a permitted return on their debt capital in excess of their debt cost.

(5) On price-cap regulation

After identifying the major problems of rate-of-return regulation, the report recommends the use of price caps to regulate HKCG before fostering new competitors in the gas market. The report argues that a price cap "is a more efficient approach from a regulatory perspective since the regulator is not given the burden of having to determine the level of `fair' return for the company" (p.49). This argument is totally erroneous and is not supported by the experience of price-cap regulation in the United Kingdom.

In the actual regulatory process, the setting of a price cap in the U.K. gas industry is not independent of the rate of return. Before determining the price cap, the regulator has to work out the allowed rate of return which can reflect the cost of capital. Once the allowed rate has been set, the regulator allows the regulated firm to raise prices by a certain percentage below the change in the consumer price index. The price cap, so determined, then allows the utility to earn sufficient returns to cover its cost of capital. If the utility increases productivity at a rate faster than the X-factor (productivity gain), then it is rewarded by earning more than the permitted returns. In fact, it can be argued that price-cap regulation is akin to rate-of-return regulation with a longer regulatory lag (of several years).

The report recommends a price-cap formula similar to the one adopted in the U.K. gas industry, that is:

RPI - X + Y

where

RPI = retail price index;

X = efficiency factor;

Y = gas cost (naphtha price) passthrough.When applying the above formula, the report ignores the fact that naphtha cost only accounts for a small portion (about 24 percent) of gas price. Furthermore, the report does not address the issue that complete passthrough might lower the company's incentive to reduce input costs. Consequent to this, the incentive for regulated firms to minimize costs under price-cap regulation is also reduced. A possible solution would be to allow regulated firms to share the benefits from securing lower input costs.

Lessons of Gas Industry Restructuring(1) The U.S. experience

The deregulation of the natural gas industry in the United States dated back to the 1970s. Faced with an energy crisis induced by price control on gas at the wellhead, Congress passed the National Energy Act of 1978, which included the Fuel Use Act, the Natural Gas Policy Act (NGPA) and the Public Utility Regulatory Policy Act (PURPA). To provide producers with enough incentives to explore and develop new gas fields, the NGPA deregulated the price of newly discovered gas.

In 1985, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) issued Order 436 which required pipelines to provide equal access to anyone requesting transportation of gas on a non-discriminatory basis. The restructuring of the pipeline business from a merchant function to primarily a transportation function culminated in 1992, when FERC issued Order 636. The stated objectives of Order 636 were to increase competition and to allocate pipeline capacity more efficiently. Total price deregulation of gas supplies at the wellhead was also completed by January 1993.

Order 636 aimed to complete the transition to a competitive natural gas industry, a transition started by the NGPA of 1978. It was believed that Order 636 would allow all natural gas suppliers, including pipelines acting as sellers of gas, to compete for gas purchasers on an equal footing. In the preamble of Order 636, FERC concluded that bundled service was the cause of a lack of comparability between an open-access transportation service and the bundled service provided by pipelines. Pipelines were accused of using their power of providing bundled service (gas sales and transportation) to enjoy a competitive advantage over other market participants. Starting from November 1993, pipelines had to render transportation service on an equal basis to all shippers of gas. Natural gas could then be purchased from a variety of third-party suppliers and transported by pipelines under some firm transportation arrangements. Suppliers of gas in the market were to provide a list of separate services, ranging from metering, storage, transportation, maintenance and repairs, etc., for their customers to choose. The unbundling of gas services, though facilitating market competition, inevitably raised the transaction costs in the market. As a result of Order 636, a pipeline's ability to balance gas demand and minimize costs has also been greatly reduced as it is no longer managing all of the capacity and storage on its system as an integrated whole.

(2) The U.K. experience

In December 1986, British Gas (BG) became the second public utility company to be privatized after British Telecom (BT). In order to speed up the process of privatization, the British government did not restructure BG's business. BG remained a virtual monopolist in the transportation and supply of gas. It was also the only U.K. purchaser of gas from the gas producers. The privatization was accompanied by the creation of a new regulatory body, the Office of Gas Supply (Ofgas). Price-cap regulation was imposed on BG in the market for small customers, while there was no explicit regulation in the market for large customers. The government believed that competition from other fuels and the policy of open access of BG's pipeline network would be adequate to reduce gas prices to their competitive levels.

Experience after privatization, however, has shown that the industry structure did not foster a level playing field for other competitors. BG was accused of practising extensive price discrimination. BG's contracts with non-tariff customers, which were almost all industrial and commercial customers, were confidential. Prices were individually negotiated, and they were set higher for those customers less well placed to use alternative fuels. BG also used its dominant position in the supply market to act strategically in its gas-purchasing policy, aimed at foreclosing entry.

After identifying the anti-competitive behaviour of BG, the Monopolies and Mergers Commission (MMC) changed its policy from relying on competition from other fuels to promoting gas-to-gas competition. The MMC report of 1988 required BG to publish its price schedules and prohibited price negotiation and discrimination. The report also requested BG to publish more information about access terms on its pipelines, which would provide more information about transmission and distribution costs to potential competitors in the supply market. When determining the transportation prices, a fair rate of return on BG's pipelines was decided by Ofgas.

In 1991, the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) conducted a review on competition in the gas industry. The review found that most of the gas contracted for by BT's competitors was used for electricity generation. Competition in the non-tariff gas market was still limited. OFT concluded that the obstacles to competition were BG's monopolistic position in the tariff market and its control of transportation and storage facilities. These resulted in cross-subsidization and price discrimination against competitive suppliers. OFT proposed full divestiture of BG and the reduction of its market share in the non-tariff market, but was willing to accept the creation of a separate transportation subsidiary as a compromise. In response to the OFT review, BG agreed to allow its access charges to be regulated by Ofgas, but failed to reach agreements on the allowed rate of return.

Faced with a tougher price cap in the tariff market and forced reduction in its market share in the non-tariff market, BG referred its business to the MMC for arbitration. The MMC published its report in 1993. Among its recommendations, it again requested that BG separate its trading business from transportation. But the government did not accept the divestiture proposal. BG was allowed to retain ownership of trading and transportation, but to operate them as separate subsidiaries with separate accounts. The government also decided to bring forward the ending of BG's monopoly over the tariff market.

Introducing Competition into the Fuel Market in Hong KongThe U.K. and U.S. experiences are essential to the introduction of competition into Hong Kong's fuel market. On the one hand, we need to avoid high transaction costs faced by fuel users as a result of the unbundling of various services, while, on the other hand, we need to prevent the dominant firm from exercising its market power over the network to foreclose competition. One important lesson to be learned from the U.S. and U.K. experiences is that structural reforms are pertinent to promoting competition. Problems encountered in the United Kingdom after privatization could have been avoided had the industry been restructured in a way to eliminate BT's foreseeable market power. Apart from open access requirements imposed on the common carrier, the determination of access terms is also of paramount importance for real competition to take place.

Studies have indicated that production and supply of gas is not naturally monopolistic and should be separated from the transportation function. Because of low cross-elasticities between alternative fuels, we need to emphasize gas-to-gas competition rather than competition between alternative fuels. HKCG should separate its production, as well as its supply business from transportation. New suppliers of gas should be able to get equal access to HKCG's pipelines, contract with gas producers (can be other than HKCG's production plants) and then make contracts on HKCG's transportation services by paying a nondiscriminatory price. The government may encourage the existing several hundreds of LPG distributors and site operators to enter into the new market. These gas suppliers could also provide storage facilities and make use of HKCG's network to distribute towngas or natural gas.

Competition in the production of gas may also be encouraged as this would lower the prices paid by end users. If natural gas is cheaper, or HKCG's existing production plants are inefficient, new entrants (including CLP) would easily enter into the market and into competition with HKCG's production business. Since the production cost of natural gas is increasing as the reserve of a gas field depletes, and the transportation cost of natural gas is also higher, it may not be cheaper compared with local production of towngas. Encouraging gas-to-gas competition also avoids the high installation cost of the three-phase electricity wiring system proposed by the Consumer Council.

The restructuring of the gas industry should involve the electricity industry. Moreover, the planning of future energy supply needs to be considered together with available supplies in China. Because of an unexpected reduction in demand for electricity in Hong Kong and from China, the two electricity companies are now running with substantial surplus generating capacities and should be required to delay their generation facility construction plans. The natural gas saved from generating electricity could then be used for other purposes, such as gas heating and cooking. The government should also encourage private companies to import energy, including electricity and gas from different places in China. This would increase the number of competitors in the energy market and reduce the demand for building new production plants. More players in the market can better achieve the conditions of workable competition and reduce the dominant firm's market power. Furthermore, some of the environmental problems associated with power generation and gas production would also be averted, and our energy supply will also be less dependent on a few large firms.

The U.S. and U.K. experiences recommend a gradual introduction of market forces into the gas industry. In order to smooth transition from a monopolistic market to a competitive market, the government may decide to open the non-residential market (of industrial and commercial users) first. At present, half of HKCG's customers belong to this class. The residential users would remain captive customers of HKCG and the U.K. price-cap regulation imposed to protect their interest. If competition in the non-residential market proves to be successful, then it can be extended to the residential market.

The Report of the Consumer Council proposes the establishment of an Energy Commission to coordinate all energy issues in the fuel market, and the Commission would be advised by an Energy Advisory Committee. But the responsibility of the Commission can be expanded to cover the electricity industry, and its role should be limited to facilitating market competition. At present, different government departments share the responsibility of regulating the fuel market and the electricity industry in Hong Kong. As the energy systems in Hong Kong expands, and better cooperation among different energy companies is becoming more and more important, we hope that the proposed Energy Commission will facilitate the planning and development of energy systems in Hong Kong and China. Under the proposed new structure in the fuel market, the Commission is charged with three major responsibilities:

(1) to decide whether the pipeline company should be subject to rate-of-return or price control;

(2) to control prices before a competitive market emerges;

(3) to detect whether the dominant firm has used its pricing policy to deter new entrants.To fulfill the first responsibility, the Commission has to avoid unjust confiscation of private property. The Commission also needs to determine the appropriate method for restructuring HKCG. Feasible alternatives like vertical separation or accounting separation should be considered carefully. This article does not address these important issues in detail, and further studies are required before introducing competition into the fuel market in Hong Kong.

Dr. Pun-Lee Lam is an Assistant Professor of the Department of Business Studies at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Table 1 Estimation of elasticities for towngas

Dependent variable=QUANTITY Variables

PRICE -0.263 (0.587) INCOME 1.531** (0.077) LPGPRICE 0.059 (0.515) CLPPRICE -0.053 (0.202) DUMMY 0.363** (0.084) CONSTANT -8.063** (0.778) R2 0.993 F 500.864 DW 1.710

Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses. **Significant at the 1 percent level. Definitions: QUANTITY = total sale of towngas in million megajoule; PRICE = average price of towngas in HK$/megajoule; INCOME = gross domestic income in HK$million; LPGPRICE = list price of LPG in HK$/kg; CLPPRICE = average price of electricity charged by CLP in HK$/megajoule; DUMMY = 0 before 1982, 1 otherwise. The dummy variable measures the impact of the Safety Report (1981) on the consumption of towngas.

All variables except the dichotomous dummy variable are expressed in natural logs.

Table 2 Risk factors and costs of equity capital

Company Beta value Cost of equity capital

CLP 0.93 19.2% HEC 0.81 17.9% HKCG 0.96 19.6%

Table 3 Actual rates of return on equity

Period CLP HEC HKCG

1964- Nominal rate of return 15.0% 15.5% 13.2% 1978 Inflation rate 5.8% 5.8% 5.8% Real rate of return 9.2% 9.7% 7.4% 1979- Nominal rate of return 22.4% 20.5% 21.9% 1992 Inflation rate 9.4% 9.4% 9.4% Real rate of return 13.0% 11.1% 12.5%